So, the word accountability is thrown around a lot in education, but the more I hear the word, the more I think we are really saying different things...

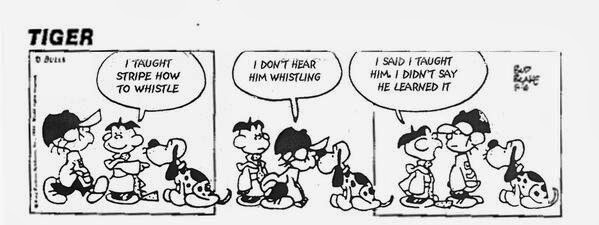

For example, teacher A wants to teach students accountability by holding firm to strict deadlines. Teacher A also does not allow redos and retakes because he/she thinks this is preparing kids for the harshness and reality of the real-world since redos and retakes aren't allowed. Teacher A believes firmly in designing assessments and activities that are hard (not necessarily rigorous) and thinks there should be some students who get high grades and other students who get low grades. Teacher A makes accountability a teacher vs. student enterprise and expects that students will naturally want to learn anything and everything just because he/she said so.

This is what teacher A believes is accountability...

Teacher B, on the other hand, wants to teach students accountability by holding them accountable to their own learning. Teacher B allows redos and retakes because he/she thinks learning is a process and sometimes there are ups and downs in this process. Teacher B acknowledges that redos and retakes are allowed in the real-world, and that for students, their everyday life is their 'real-world.' Teacher B also believes in designing and engineering highly challenging and rigorous learning experiences with appropriate levels of support. Teacher B holds his/her kids accountable by not allowing them to do anything but their best work and by not accepting anything less than their best. Teacher B put kids in charge of their progress and empowers them to own their learning.

This is what teacher B believes is accountability...

So, which teacher are you?

For example, teacher A wants to teach students accountability by holding firm to strict deadlines. Teacher A also does not allow redos and retakes because he/she thinks this is preparing kids for the harshness and reality of the real-world since redos and retakes aren't allowed. Teacher A believes firmly in designing assessments and activities that are hard (not necessarily rigorous) and thinks there should be some students who get high grades and other students who get low grades. Teacher A makes accountability a teacher vs. student enterprise and expects that students will naturally want to learn anything and everything just because he/she said so.

This is what teacher A believes is accountability...

Teacher B, on the other hand, wants to teach students accountability by holding them accountable to their own learning. Teacher B allows redos and retakes because he/she thinks learning is a process and sometimes there are ups and downs in this process. Teacher B acknowledges that redos and retakes are allowed in the real-world, and that for students, their everyday life is their 'real-world.' Teacher B also believes in designing and engineering highly challenging and rigorous learning experiences with appropriate levels of support. Teacher B holds his/her kids accountable by not allowing them to do anything but their best work and by not accepting anything less than their best. Teacher B put kids in charge of their progress and empowers them to own their learning.

This is what teacher B believes is accountability...

So, which teacher are you?